Hello!

I hope that many of you have gotten to take some time off over the past few weeks to rest and reflect on 2023. The Thanksgiving - New Year’s time period is my favorite time of year, as I get to spend more time with my broader family and it becomes socially acceptable to eat cookies with/for breakfast.

It is also the time of year when I devote more time to thinking about the broader state of EdTech. For the past 2 years, I’ve turned these thoughts into essays. In 2021, I focused on trends picking up steam across the space (parts 1 and 2). Last year, I got to work with EdSurge on some predictions for the year to come.

This year, I’m going to do a little bit of both. This essay focuses on the trends from the past year. In the next couple of weeks, I will write a follow-up with some predictions about what I think will happen in 2024.

This exercise is daunting. So much happens over 12 months that it is impossible to encapsulate everything. But I hope that these reflections resonate with many of you. For those for whom it doesn’t: see you in the comments!

With that, on to the year in review!

Did someone forward you this email? Subscribe for Weekly Updates on the EdTech industry from ETCH

2023 in short

This year felt…unsteady in the EdTech market. The top end of the venture market - venture rounds of $100M or more - fell off a cliff. After 16+ deals of that size in 2022, not a single company publicly disclosed a $100M+ round this year.1 More name-brand companies self-destructed (4) than there were new unicorns crowned (1) or large exits of venture-backed companies (0). That one new unicorn, Replit, has largely pivoted away from its EdTech origins to focus on the more lucrative software development tools market.

The IPO market remains frozen unless you are slinging advanced processor designs, falafel bowls, or hipster sandals. Lack of access to public market capital has not (yet) hamstrung a properly operating late-stage EdTech company, but the freeze hurts valuation benchmarking and keeps capital from being re-deployed into the early-stage ecosystem. We can, and should, hope for a new wave of innovation when companies like Guild, Multiverse, Emeritus, Andela, GoGuardian, Masterclass, Handshake, Amplify, and Newsela exit (either publicly or privately). But that did not happen this year.

The clock struck midnight for the Online Program Management (OPM) industry’s time at the regulatory ball. Reliant for 10 years on a piece of informal regulatory guidance, the Education Department made enough noise about a new set of compliance standards to scare away 2 of the 5 major US players in the space while setting a third on a probable path to bankruptcy.2

Suffice it to say there is a fair amount of anxiety running among those with a financial interest in the Education market.

But! The year was not a total wash.

Of the 15 major public EdTech companies, 8 - Duolingo, Stride, Coursera, Kahoot!, Nerdy, Docebo, Bright Horizons, and Udemy, in that order - beat the S&P 500’s 25% annual growth.3 2U, Chegg, and Wiley had tough years, but each of the 12 others saw their stock price grow in 2023.

The market for EdTech venture funds has also never been greater. 5 of the 12 EdTech-specialist institutional VCs announced new, $100M+ funds this year.4 These 5 follow 3 $100M+ funds announced in each of 2021 and 2022, all six of which are still in active deployment. Further, corporate strategics Workday and Imagine Learning committed new capital to their internal venture funds, Workday adding $250M and Imagine adding $50M for a fund focused specifically on AI.

And private equity remains ever-present in the EdTech market, delivering 23 buyout deals in honor of the year 2023. These deals ranged from the lower middle market to Mega funds like Providence Equity (Accelerate Learning), TPG (Asia Pacific University and Outcomes First), Bain Capital (Meteor Education), Goldman Sachs (Kahoot!), Vistria (Really Great Reading Company), and General Atlantic (Arco).

Financial results are not necessarily the end-all, be-all of how an industry is performing - I’ll get to some more qualitative observations of where we made progress (and backtracked) this year. But I do find that they help ground the conversation, setting a quantified record for us to build upon in future years.

As such, I’d like to further explore this year’s venture funding environment before digging into a selection of the year’s broader themes.

Where is all this data coming from?

You may have noticed quite a few numbers without linked citations in the above section; this pattern will continue below. I am excited to say that these numbers came from my own, *hand-curated* database of EdTech financial transactions. I will have more to say - and show! - about this database in the next few weeks.

For those who are interested, ETCH Founding Members (the $200/year option) can access the beta version right now(!) by clicking the button below. You can check your current membership status by visiting etch.club, clicking your user profile, and choosing “manage subscription.”

Team and Enterprise access can also be arranged by emailing matt@etch.club or responding to this note.

2023 by the numbers

This year I used the ETCH funding database (see above for more) to track 335 institutional VC rounds, 137 acquisitions, 23 buyouts, and 6 new venture funds associated with the EdTech space.5 These deals ranged in size from Liledu’s $130K seed round to the $800M that Instructure paid to acquire Parchment.6

Venture capital funds deployed at least $3.02B across these 335 VC rounds. This capital went to companies headquartered in 46 different countries. Just 33% of the deals (and 45% of the dollar volume of funding) went to companies headquartered in the US. India (14% of companies, 12% of funding), the UK (12% of companies, 8% of funding), Germany (4% of companies, 5% of funding), and France (4% of companies, 3% of funding) round out the top 5 most active venture markets for EdTech.7

To help visualize the last paragraph:

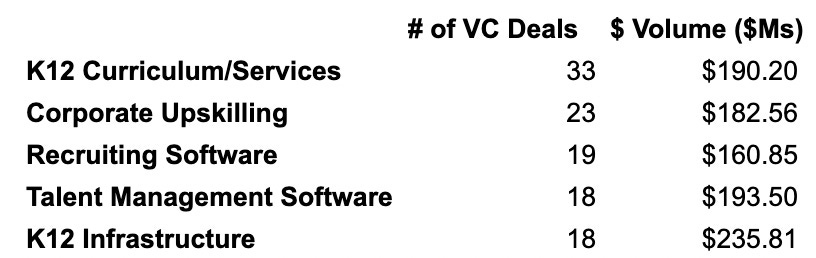

The most popular category of companies to receive venture funding this year was K12 Curriculum and Services - companies that sell to or are trying to replace K12 schools - with 33 different venture rounds and $190M of associated dollar volume.

K12 Infrastructure providers - think of financial tools like Classwallet and non-academic software like BusRight - actually raised the greatest dollar volume of funding, with $235M raised across 18 venture rounds. But, since venture capital is oriented around a power law distribution, I prefer to look at deal volume as a barometer for where the puck is headed in EdTech funding.

Whatever your preference, these stats should be a reminder that the K12 market is big, sticky, and still receiving a lot of investor attention.

However! Plenty of other categories received attention this year too. The top 5 by deal volume were:

Also receiving votes for prom queen (categories with 10+ venture deals this year) were Training Providers (design and provide workforce training, excluding bootcamps), Student Financing, Assessment, VR, Tutoring Marketplaces, and Test Prep.

So, what does this all mean? How did these flows of capital affect the EdTech market?

The Predictions

Last January I worked with EdSurge to publish predictions on what might happen in 2023. These predictions were:

EdTech buyers and sellers will grow more sophisticated

A company that specializes in data analysis will reach breakout stage

EdTech will become more global

I would give myself a B for these predictions. I think the themes are broadly right, but I’m not sure they were THE themes of 2023. With the benefit of hindsight, I would reframe last year’s predictions to focus on three areas:

1. AI positively enabled new tools in the Tutoring and Language Learning markets but was a non-essential R&D project everywhere else:

2023 will be remembered as the Year of AI. I’d be willing to bet that > 80% of EdTech companies experimented with the technology, that more than 100 EdTech companies published a press release about it, and that < 5% of EdTech users leveraged AI to actually learn something.

AI is neat. You’ve probably read a lot about AI in education this year, even if you don’t work in the industry. Duolingo’s use of OpenAI’s capabilities to extend the lifetime value of their most dedicated language learners is truly magical, from both a product and business model perspective. In the tutoring space, synthetic tutors make it easier than ever to support both struggling and overachieving students before they lose focus.8 (Except in Math. Math is hard, even for robots.)

But Language Learning and Tutoring are the only sub-sectors of education where AI made an immediate impact.

In the Homework Help category, Chegg’s stock price bombed. Flashcards, another category seemingly made for AI, had no winners emerge and basically no interesting news after Quizlet’s OpenAI partnership. No one can decide if plagiarism detectors work, not even OpenAI. The only publisher with a legitimate claim to have AI as a core feature of a core product is Newsela, which started incorporating machine learning long before ChatGPT came around.

That last paragraph sounds more dour than I mean it to be. I *am* excited by AI’s potential. There has never been a better time to learn a new language than right now. And I believe AI will drive a sea change improvement in early literacy sooner than you think, with no fewer than 10 companies raising venture funding in 2023 to tackle the problem.

Looking ahead to 2024, I hope the volume of AI headlines slows down so that we can focus on real, demonstrable student impact rather than R&D press releases.

2. The EdTech Ecosystem saw 0 big liquidity events for early investors and 4 notable self-destructions of EdTech companies, which will put stress on capital markets moving forward:

2A. Lack of liquidity

While AI grabbed the headlines this year, the story among EdTech investors was liquidity, or lack thereof. There were some big private equity-led deals - such as the Lego-consortium buyout of Kahoot!, Instructure’s acquisition of Parchment, and Discovery’s acquisition of Dreambox. And a few deals for well-known brands - such as ParentSquared’s acquisition of Remind, Curriculum Associates’ acquisition of Soapbox Labs, Perdoceo’s acquisition of Coding Dojo, and Go1’s acquisition of Blinkist.

These deals are important. They highlight that the traditional paths to EdTech exits - large, established EdTech companies (“strategics”) and PE funds - are alive and well.

But they did not deliver the same type of “return the fund” results to early investors and employees as other transactions from recent years - such as Lego’s $875M acquisition of Brainpop, 2U’s $750M acquisition of Trilogy, LinkedIn’s $1.5B acquisition of Lynda.com, and the IPOs of Coursera, Duolingo, and Udemy.

Early investors and employees of companies with large exits provide the bulwark of support for each new generation of EdTech innovation. It is hard for this cycle to continue without consistent exits.

This will not be an *immediate* problem. There is enough dry powder among the institutional VCs, philanthropic organizations, and student loan administrators to keep things moving for now. But a year without recycling social and financial capital back into the early-stage part of the ecosystem does create stress.

2B. No exits, and 4 big companies fell apart

Speaking of capital not being recycled back into the ecosystem, several of the industry’s biggest companies and/or highest-potential exits proactively shot themselves in the foot (feet?) this year.

Byju’s is the headliner of this list of self-owns, which also includes Bitwise, Frank, and 2U. Let’s review the case against each, ordered by how quickly each company went from good news to very, very bad news.

1. Bitwise: A bootcamp darling, Bitwise raised $80M in February to build coworking spaces in blighted areas of tier-3 US cities (in retrospect, a truly incredible confluence of low-margin, not-software opportunities).

Authorities are still sorting through how many different kinds of fraud were committed, but by June, the company ceased to exist. Time to self-destruction: ~4 months

2. Frank: Founded in 2016 with the (noble!) intent of making the US’ post-secondary financial aid system easier for students to navigate, JP Morgan bought Frank for $175M in September 2021.

Unfortunately, the user numbers Frank’s leadership team provided to JP Morgan to drive this valuation were made up by a data science professor paid explicitly to generate fake data. The orange jumpsuits have not been handed out yet, but no one you know will be using Frank’s services anytime soon. Time to self-destruction: ~16 months

3. Byju’s: Byju’s ended 2022 as the most valuable EdTech company in the world, with a private market valuation almost 3X second-place Pearson’s public market capitalization at the time. I actually predicted that they would still be the most valuable EdTech company at the end of 2023, despite a growing set of reports that the company had overextended itself during COVID.9 I figured that the company would install new leaders and retrench.

Instead, they doubled down on bad decisions, forcing 3 respected board members and their auditor, Deloitte, to resign from their involvement with the company. Byju’s ended the year hustling for cash, and their largest shareholder has marked them down at least 86%. It now looks more likely that they will go down in history as the company that gave $500M to a 23 year-old Miami stocks bro than that they will become a forever-brand in Education. Time to self-destruction: ~17 months

4. 2U: The company that created the Online Program Management (OPM) category, 2U is the saddest entry on this list.10 You, and Liz Warren, may quibble with the OPM industry’s role in higher education, but 2U did not make any obviously fraudulent/irresponsible decisions to earn their place in this list. Instead, their error was a debt load that could not be overcome by company strategy. 2U’s stock peaked in mid-2018, as the company started realizing the benefits of the short courses and internationalization that came with their 2017 acquisition of GetSmarter. This encouraged the company to take bigger and bigger swings, paying $750M for Trilogy in 2019 and $800M for edX in 2020, mostly in cash.

Transparently, I thought, and continue to think, that these moves formed a pretty reasonable product strategy - the companies are structurally different, but Coursera rode a well-known consumer brand + diverse set of course/program offerings to a 62% gain this year! But 2U’s multiyear cashflow cycle and 1:1 revenue:debt ratio (in a market with rapidly rising interest rates) proved too concerning for public market investors to stay bought in. Ending 2023 with their stock price down 79% for the year, the company’s most likely outcome now appears to be bankruptcy and/or a takeover by private equity.11 Time to self-destruction: ~67 months

4B. A narrative built around Chegg, who saw their stock price decline 56% this year, also works here. However, Chegg’s immediate financial position is not quite so dire as 2U’s, so I’m still not ready to hop on board the “ChatGPT killed Chegg” train.

Candidly, this section sucked to write. Every industry took its lumps during/after COVID, but EdTech’s COVID hangover feels particularly acute. It will take some strong exits and/or really strong public market debuts to get the EdTech hype train back on its tracks. I am hopeful for this in 2024, but not planning on it.

3. The organization that invented seat time is now putting its weight behind competency-based education (CBE)

The best way to make money in education today is to put a new student’s butt in an open seat.

It pains me to write that sentence, but it is unequivocally true. And it has been true for upwards of 100 years because of the way we measure learning progress: the Carnegie Unit and Hour.

Initially proposed in 1906 and widely adopted by 1911, the Carnegie Unit cemented what I impolitely call the “butts in seats” approach to funding education. By design, it forced students to spend over 3,000 hours spread across 8+ years to earn a post-secondary degree. Also by design, the easiest way for schools to access government education funding was to adhere to these same standards. Getting, and keeping, a student enrolled drove revenue for schools.12

The Carnegie Unit deserves credit for bringing a healthy amount of standardization and accessibility to education in its time. But we now have the tools and technology to measure learning progress in a more sophisticated way than how long students keep their - often fairly uncomfortable! - seats warm.

And yet, I have long felt like CBE had more approval from education people than it had actual momentum. CBE had a media moment in the mid-2010s, but the number of universities offering CBE degree programs has been flat since at least 2015.13 Even among the 600 institutions that do offer CBE degrees, the majority (53%) have < 50 CBE enrollments. Stories of CBE failing to catch on abound in K12 too – like CBE’s relative failure at high schools in Maine.

The CBE movement has many evangelists and spawned the well-regarded Competency-Based Education Network (CBEN). However, it has not yet offered a direct challenge to the Carnegie Unit.

Now, the Carnegie Foundation’s education arm - the same entity that drove the adoption of the Carnegie Unit 100 years ago - is putting their social and financial capital behind a change explicitly focused on “shift[ing] schools’ focus away from traditional ‘seat time’ requirements and towards more accurate measures of mastery over academic content.”

A competency-based future is a future with a whole new paradigm of funding incentives. With luck, this paradigm will be built around results - moving a learner from point A to point B rather than just getting their butt in the chair.

In turn, this means schools - and the EdTech providers that serve them - can spend more of their own budgets on moving learners from point A to point B rather than on marketing.

I cannot emphasize enough the importance of this shift for both student and financial impact. I have seen dozens of EdTech products over the past 10 years that could show legitimate student impact but simply weren’t viable businesses in a world that valued butts over results.

To be clear, these companies did not become viable businesses in 2023 - we have a long way to go before we can start building with the assumption of competency-based funding incentives. But Carnegie and ETS’ clear, repeated support for CBE means we may look back on 2023 as a milestone year that steered the market in that direction.

In Conclusion

2023 was a whirlwind.

There are many other trends one could reasonably advocate for as the EdTech themes of 2023. Among others, I would highlight concern about the global decline in K12 achievement tests, renewed debate around school choice in the US, resounding growth in support for the Science of Reading, signs of increased private and public interest in credentialing, a (forced) turning of the page from the OPM era to the DIY era of online degree programs, high profile conflict over the societal role of universities and university leaders, and growth in the apprenticeships market (or maybe not).

But AI, self-inflicted wounds, and moving away from seat time are the trends that stick out the most *to me.* Not because they are the sexiest headlines (although AI did drive a lot of headlines), but because they provide the best context with which to think about the future of EdTech.

The funding environment looks like it is about to get a lot tighter, with many more companies exiting for sub-par returns or closing shop entirely. But there is now a whole new world of AI tools available inexpensively to startups. And major philanthropic players are sowing the seeds of national-scale change in the way education is evaluated. It is not too much of a leap that global-scale change might follow.

The entrepreneurs who are quickest to figure out how to navigate this new environment will thrive. And observers like me will be on the lookout to make sure you know their stories.

Enjoyed this essay? Subscribe here to read the ETCH’s weekly newsletter on the EdTech ecosystem

It is *likely* that Amplify’s Series C funding round was greater than $100M, but the company did not disclose the amount raised. I also did not include Cengage’s $500M fundraise or EQuest’s $120M fundraise as both included a non-disclosed amount of debt in their raises and were orchestrated by more traditional PE funds rather than VCs. Even if you do include those 3 rounds, the drop-off from 16 to 3 is steep!

I do not expect these standards to be implemented in 2024 due to the US election. They place a substantial operational burden on universities, whose employees form the core of democratic voter bases across the country, particularly in non-urban areas. I suspect there will be a lot of quiet lobbying to delay any further action on OPM regulation until 2025 at the earliest.

This list excludes publicly traded online universities and leadership/staffing companies. These companies are strategic players in the EdTech industry, but are less useful as barometers for the valuation of startups. Further, Kahoot!’s stock price increase is, admittedly, a little bit of a red herring given they will be taken private in 2024. But, if you invested a $1 in Kahoot! on 1/1/23, you would have made money holding onto it until 12/31/23.

I define “institutional VCs” as VCs whose primary mandate is to return capital to LPs and have publicly disclosed at least one fund of $50M or more. The EdTech ecosystem is fortunate to be supported by a number of philanthropy-minded investors and emerging venture fund managers (VCs with funds of < $50M), but the scale and incentives of these two categories are tricky to track and, thus, hard to use as a barometer for the overall health of the ecosystem.

I define EdTech as inclusive of Early Childhood, K12, Higher Ed, and Workforce companies. “Workforce” is inclusive of any tool that directly impacts the career development of an employee (e.g. talent management software, training/certification providers, and recruiting platforms are included; HRIS tools are, generally, not). Further, to qualify for my funding database, companies must raise funding from at least one verifiable institutional investor.

This is a somewhat arbitrary categorization, but I think it does a good job capturing the field of companies that an EdTech-specialist investor would consider investing in.

It is possible that Discovery paid more than $800M to acquire Dreambox Learning, but the acquisition amount was not disclosed.

There is also a healthy amount of early-stage activity in Singapore, the Netherlands, and Spain, but the dollar volume of funding is on the smaller side.

“Synthetic” may sound funny at first blush, but it has rapidly grown on me as a descriptor for AI-driven interactions.

It turns out this crown will go to Duolingo, who finishes 2023 with a market capitalization of $9.53B.

2U is publicly traded, so it isn’t the best fit for the case I’m trying to build about capital cycles driving early-stage innovation. But current and former 2U employees are pretty active in the early-stage ecosystem and the company’s fall feels like it reverberated across the industry in a similar/greater manner than the other examples, so it felt worth including.

2U’s -79% change in stock price was current as of 12/27/23 (same basis as my other stock price references).

One additional piece of nuance here is that students are at their most profitable in the early years of their education - think college intro courses, where one professor lectures to 100+ students at a time. There exists a perverse incentive to keep students in an endless loop of these courses. I don’t think many colleges orchestrate this loop intentionally, but it does manifest in the endless loop of remediation courses that some students get stuck in.

There is no official record of institutions that offer CBE programs, but the Competency Based Education Network (CBEN) estimated that there were 600 universities offering competency-based degrees in 2015 and 2022. I am a fan of CBEN and think they do good work, but it is in their interest to inflate the number of CBE-providing institutions as much as possible. Given that that number has not moved in 7 years, I feel reasonably comfortable saying that growth is flat.

thanks for the recap, looking forward to the predictions for '24!

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=QZZ3PpTVsqM